Google's existential business risk is real

Will they go wobbly like Kodak, Sears, Blackberry and Sun, or survive and thrive?

Will Google’s search-based ad Business Collapse? Should it? Should Google speed up the process or slow it down? How did Kodak lose to FujiFilm? I explore these and many other examples before concluding.

The concept of existential risk is simple.

The lack of sufficient food to survive their first winter threatened the existence of the colonists who landed on Roanoke Island in 1587. It was an existential risk.

The yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia in 1793 resulted in approximately 5000 deaths and a mass exodus of residents. Yellow fever posed an existential threat that was made worse by a lack of understanding about disease transmission.

Natural disasters, economic downturns, criminal activity, geopolitical instability and technological paradigm shifts can all pose existential risks to businesses and other entities.

Existential is an adjective. Adjectives relate to entities, nouns.

Entities can be abstract or conceptual, as in life, industries, businesses, forms of government, religions. The entities can also be simpler as in a belief or a person.

Existential pertains to the very existence of the entity.

What’s this have to do with Google’s success or failure?

Search-based ads are a good half of Google’s revenue stream and various Large Language Model (LLM)-based bots (such as ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, and Grok — referred to below as SmartBots) could essentially wipe out that revenue for Google if and when certain conditions are met, unless, of course, Google beats the competition to the punch and drives a new business model for a world where SmartBots become the near-constant companions that endear themselves to their friends (users.)

Someone should own the new segment defined by the SmartBot as companion and assistant. Google can’t afford to let others take over that spot. But will they?

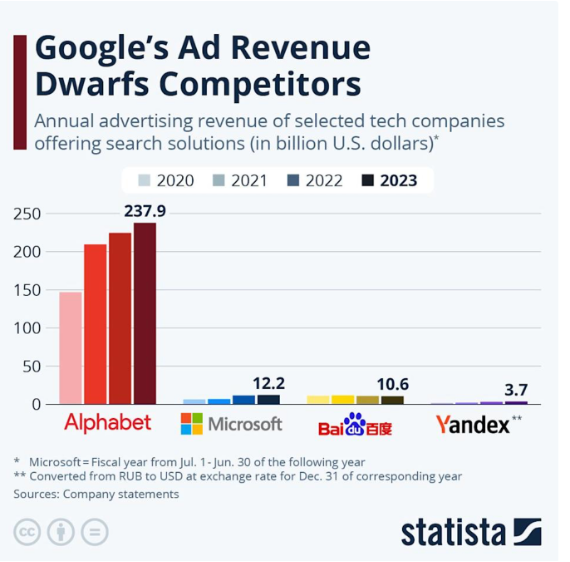

Set the stage: In 2023, 57 percent of Alphabet’s revenue came from search-based ads.

Total 2023 Alphabet revenue was $307.39 billion

Google ad-based revenue $237.9 billion (77.4% of total)

Google search-based ads were $175 billion (57% of total)

And let’s remember: this is really a big space for Google versus everyone else (including the courts.) Google owns the search space:

Source: Statista, 2024

Existential risk issues face both ways

The SmartBot existential risk for Google is simple: SmartBots could destroy the Google search based advertising business if users perceive the SmartBots as delivering a better focus on their needs versus Google’s current focus on advertisers’ needs.

The SmartBots also face an existential risks.

Their current business models don’t generate enough revenue given their operating cost. Could the SmartBot companies shift to advertising-based revenue model to cover their huge operating costs?

Alternative outcomes: Let’s develop some historical examples of firms that faced existential business risks and survived or failed. How and why did they drive the outcome?

Historical Examples

Kodak vs FujiFilm

The Real Kodak Story Beyond the Smartphone Myth

1. A vertically integrated giant in the 1980s.

Kodak dominated consumer photography with a “chemistry-as-a-service” model: sell film, charge for processing, sell paper for prints. Margins were high, and its vertically integrated structure made it a global powerhouse. It was a great money machine!

2. Structural cracks in the 1980s–90s.

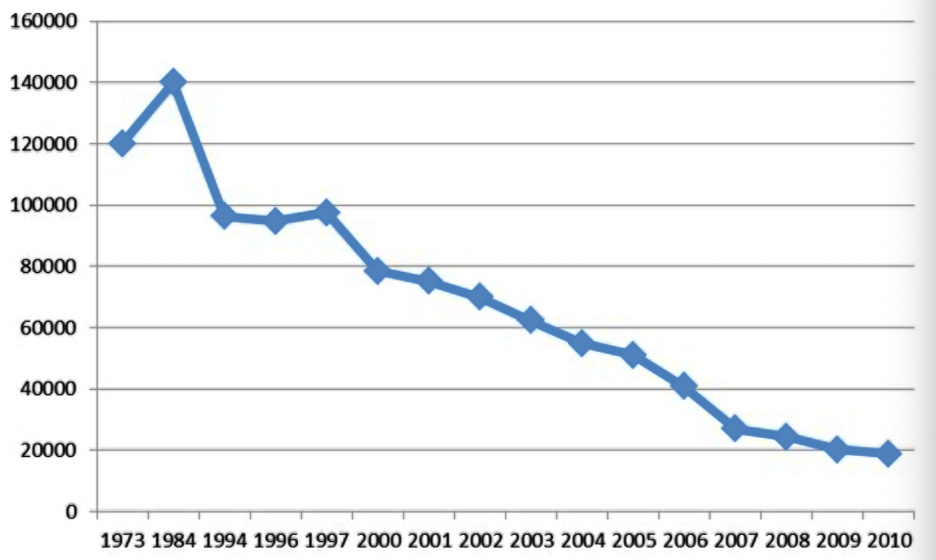

Even before digital disruption, Kodak’s foundation was eroding. Check out their headcount. These numbers showed a firm in deep trouble before anyone could spell digital.

Source: https://disruptiveinnovation.se/wp-content/uploads/Kodak-employees.png

Kodak was facing:

Aggressive competition from Fuji undercut film prices globally.

Retail consolidation (Walmart, Costco, drugstore chains) squeezed Kodak’s once-premium pricing.

Photofinishing economics changed, with one-hour labs reducing Kodak’s processing margins.

Cost burdens (notably retiree healthcare and pensions) weighed heavily.

Currency shifts (especially a strong yen) tilted the playing field.

Kodak responded with massive layoffs and restructurings throughout the 1990s — long before smart phones existed.

3. Digital disruption was an accelerant, not the root cause.

By the early 2000s, Kodak was already weakened. The rise of digital cameras and later smartphones didn’t initiate the decline; they accelerated it. What was once a stable, recurring revenue stream collapsed as consumers stopped printing photos altogether.

4. The cultural and financial bind.

Kodak wasn’t blind to digital — it invested heavily and even invented much of the core technology. But its dependence on film and printing profits (and shareholder expectations of continued dividends) made pivoting fully to digital extraordinarily risky. Kodak was stuck: move too slowly, and die from disruption; move too fast, and collapse in the face of investor revolt.

5. The true lesson.

People say Apple killed Kodak. The data does not support that conclusion: Kodak was in the death throes before the iPhone appeared. Structural erosion hollowed out the business decades before digital photography went mainstream. By the time Apple, Samsung, and Google disrupted consumer photography, Kodak no longer had the financial or strategic flexibility to respond.

Fujifilm, on the other hand, survived and thrived. They maintained a relatively stable employee population – even as they were exposed to a lot of churn for new skills as the company reinvented itself during the 30 year period of existential threat.

This perspective makes the divergence unmistakable: Kodak downsized drastically to cut costs, but never built new, sustainable growth engines.

Fujifilm (Stability through Diversification)

2000: CEO Shigetaka Komori embraces digital disruption, announces diversification drive.

2003–2010: Expansion into LCD films, healthcare, cosmetics, and advanced materials.

2010s–2020s: Workforce steady around 70–75k, supported by diversified revenue streams.

2024: ~72k employees, global tech conglomerate across healthcare, imaging, and materials.

Pattern: Fujifilm preserved scale by repurposing film-era expertise into growing industries.

Here’s the 2025 snapshot dashboard:

Both Fujifilm and Kodak have ~17–18% of revenue from photography.

But Fujifilm’s base is ~$32B total, with photography at ~$5.4B.

Kodak’s base is only ~$1.1B, with photography at ~$200M.

This makes the absolute scale of their photography businesses vastly different, even though the percentage looks similar.

Having drawn out the Kodak/Fujifilm lesson, let’s now learn from other transformations before coming back to Google’s future.

Success stories in the face of existential risk

IBM (1990s – early 2000s)

Crisis: Mainframe revenues collapsed in the late 1980s/early 1990s, and IBM posted a record $8 billion loss in 1993.

Transformation: CEO Lou Gerstner shifted IBM from a hardware-centric company to a services and consulting powerhouse (IBM Global Services).

Outcome: By the early 2000s, IBM was one of the most profitable services/solutions companies. Today, IBM is still alive largely on the strength of that pivot.

Why it worked: Gerstner had backing to cut dividends, shed legacy businesses, and invest in new services — shareholders hated it at first, but it bought survival. Subsequently, IBM successfully worked through multiple significant pivots.

Fujifilm (2000s – present)

Crisis: Film sales collapsed even faster than Kodak’s.

Transformation: Management aggressively diversified into healthcare (medical imaging, pharmaceuticals), cosmetics, advanced materials, and digital imaging.

Outcome: Today, photography is <20% of revenue, with healthcare and materials growth far exceeding film declines. Fujifilm is several times larger (by market cap) than Kodak.

Why it worked: Willingness to use “film profits” as a war chest for diversification, rather than just protecting margins.

Google take-away: use search-ads profits to fund major diversification rather than just protecting revenue streams.

Apple (late 1990s – 2000s)

Crisis: Apple was weeks from bankruptcy in 1997.

Transformation: Under Steve Jobs, Apple shed legacy products, doubled down on design-led computing, and bet big on new ecosystems (iPod, iTunes, then iPhone).

Outcome: One of the greatest corporate comebacks in history.

Why it worked: Ruthless product cuts, rapid innovation cycles, and a willingness to bet on entirely new categories (music, phones).

Google take-away: Like Apple, ruthlessly cut existing products and business models, drive rapid innovation cycles and be willing to bet on entirely new business categories.

Microsoft (2014 onward)

Crisis: By 2013, Windows/Office revenue growth rate was eroding, and the company was seen as stagnant.

Transformation: Satya Nadella pivoted Microsoft to cloud-first, subscription-based services, cutting “Windows at the center” as the strategy.

Outcome: Market cap grew from ~$300B in 2014 to >$3T today. Azure cloud is second only to Amazon Web Services

Why it worked: Courage to de-emphasize the legacy cash cow (Windows) and embrace cannibalization in favor of growth.

Google take-away: Like Microsoft, de-emphasize legacy cash cow.

Netflix (multiple pivots)

Crisis moments:

Early 2000s DVD rental by mail looked fragile as Blockbuster dominated.

Late 2000s streaming was a huge gamble that threatened DVD cash flow.

Mid-2010s original content meant burning billions.

Transformation: Each time, Netflix “killed” its own existing model to push the next one.

Outcome: Netflix remains a global entertainment leader but faces heavy competition (Disney, Amazon, Apple). Growth has slowed post-2022.

Why it worked: Willingness to cannibalize itself repeatedly rather than protect the old model.

Google take-away: Like Netflix, Google has to cannibalize its current ad-based business before its SmartBot business has grown as large as what it should be replacing.

Nokia (2010s – telecom equipment pivot)

Crisis: From mobile handset giant in the 2000s, Nokia collapsed after Apple/Android. By 2013, it sold its phone business to Microsoft.

Transformation: Doubled down on networking infrastructure (via acquisition of Alcatel-Lucent in 2016).

Outcome: Today Nokia survives as a major telecom-equipment provider, not a consumer brand.

Key move: Walked away from its famous core business to survive in B2B markets.

Nintendo (2000s – 2010s)

Crisis: After the GameCube and later the Wii U struggled, analysts predicted decline.

Transformation: Invested in unique gaming experiences (Wii motion controls, Switch hybrid console) and broadened into mobile + IP licensing (theme parks, film).

Outcome: As of this year, ~140 million Switch units sold. Switch is one of the best-selling consoles ever; Nintendo has record profits.

Key move: Reinvented its value proposition instead of chasing the “arms race” of Sony/Microsoft.

Adobe (2010s – subscription pivot)

Crisis: Selling boxed software (Photoshop, Illustrator) was increasingly unsustainable with piracy and long upgrade cycles.

Transformation: Moved to Creative Cloud subscription model (2012–2013).

Outcome: After initial stock dip, Adobe grew into a multi-hundred-billion dollar firm with recurring SaaS revenue.

Key move: Risked angering customers and shareholders with a business model shock — but it worked.

Google take-away: Like Adobe, Google may have to anger its customers (advertisers) short term.

Corning (2000s)

Crisis: Traditional glass and ceramics faced commoditization; telecom crash in 2001 nearly wiped it out (optical fiber business collapse).

Transformation: Invested in specialty glass (Gorilla Glass, LCD substrates, life sciences).

Outcome: Gorilla Glass became ubiquitous in smartphones; Corning remains strong.

Key move: Leveraged materials science R&D into entirely new consumer and industrial markets.

Google take-away: Like Corning, Google should leverage AI R&D into entirely new consumer and industrial markets.

Survivor’s Lessons

They survived because leadership either convinced shareholders to endure pain, or simply ignored Wall Street’s screams long enough to transform.

Companies can survive massive disruption if they:

Are willing to sacrifice short-term profits to fund transformation.

Have leaders strong enough to resist shareholder revolt.

Have “adjacent capabilities” (e.g., IBM → services, Fujifilm → chemicals/healthcare, Microsoft → cloud) to pivot into.

Lessons Across These Cases

Sacrifice Sacred Cows: IBM exiting hardware, Nokia exiting phones.

Bet on New Models: Adobe subscriptions, Netflix streaming, Apple iPhone.

Leverage Core Strengths: Corning using materials science, Fujifilm using chemical expertise for healthcare.

Manage Shareholder Revolt: Most of these saw a stock dip before the strategy paid off. Management had to ride it out.

It’s not that easy, is it? There’s also a long list of firms that made radical changes in business strategy but still essentially failed. For example: Sears (2000s–2010s), BlackBerry (2010s), Yahoo (2000s–2010s), General Motors (2000s), Sun Microsystems (2000s). I’ll leave the failure analysis (beyond Kodak) to future papers.

What about Alphabet and the existential struggle with SmartBots?

Can Alphabet win? Yes. Can they lose? Yes. Likewise, can the SmartBots win? Yes. Can they lose? Yes.

Here’s my reading of Alphabet’s shot in the struggle with SmartBots

1. Leadership and Vision

Strengths: Sundar Pichai & Ruth Porat openly acknowledge the challenge. They’re restructuring around Gemini (Google’s SmartBot — AI assistant platform) and cloud. Google DeepMind & Google Research remain top-tier in innovation.

Weaknesses: Public messaging still overemphasizes protecting core search ads (“AI overviews” designed not to lose clicks). Much of leadership focus feels defensive.

Caution: There are three key revenue numbers in play here: Google search-ad revenue, Google SmartBot revenue and others’ SmartBot revenue.

I’m comfortable predicting that long term, SmartBot providers will own the revenue stream currently enjoyed by Google. Some will go to other SmartBot providers (OpenAI, et al) and the rest to Google. But that picture is very unclear. As non-Google providers get better and better, Google’s lack of a clearly articulated, publicly disseminated vision for where all that is going concerns me. Google must primarily push the market ahead rather than defending its current cash cow.

They haven’t publicly articulated their long term revenue mix aspirations across Google and others’ SmartBots and search ad revenue. I haven’t heard a clear message that “the future is now.”

Rating: Troubled.

2. Willingness to Cannibalize

Strengths: Launching Gemini, embedding AI answers into Search (despite cannibalizing links). Building hardware (Pixel, Tensor chips). Cloud revenue now 10%+ of Alphabet total and growing.

Weaknesses: Reluctant rollout of AI in Search (slower than OpenAI + Microsoft). Clear hesitation: they know every AI answer risks cannibalizing the ad click model.

I’m concerned. I am willing to assume the ad-click model slowly dies a painful death. (A fast death could occur instead but that’s less likely.) How does Google help speed the death of the ad-click model to exploit a new position of dominance of SmartBots? I fear they fear that, if they talk about the future, they will accelerate the flight of users away from the ad-click model. Google has to lead on the vision and execution of the replacement else they run a great risk of being the next Kodak. Or Intel. Or …

Rating: Hesitant cannibalization.

3. Resource Allocation

Strengths: Massive Google R&D spend (~$45B annually). Investing in Google Cloud, Waymo, AI infrastructure.

Weaknesses: Still almost 80% of profit comes from ads. Cloud, Waymo, and “Other Bets” aren’t yet delivering profit scale. Internal churn (e.g., layoffs, project cancellations) undermines bold bets.

Rating: Strong investment, but not yet shifting profit base.

4. Customer Ecosystem Adaptation

Strengths: Strong AI developer ecosystem, Android + Play Store, Chrome dominance.

Weaknesses: Consumer shift to ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, TikTok for search-style queries shows cracks. Google hasn’t built a “new ecosystem” beyond Android, and Gemini isn’t yet sticky.

Rating: At risk.

5. Investor/Board Alignment

Strengths: Alphabet has the financial muscle to absorb hits (>$100B cash). Investors tolerate “Other Bets” as long as Search cash machine runs.

Weaknesses: Market punishes stock dips on AI threat news. There’s shareholder nervousness if Search margins dip. Could lead to Kodak-like paralysis.

Rating: Neutral but fragile.

6. Internal Talent & Skills

Strengths: Still attracts top AI researchers, owns DeepMind, world-class infra talent.

Weaknesses: 2023–2025 layoffs shook morale. Many AI stars defecting to OpenAI, Anthropic, start-ups. Bureaucracy slows deployment.

Rating: Mixed, drifting toward negative.

Overall Outlook

Today, Alphabet is in the “Yellow Zone”: still dominant, still wealthy, but showing hesitation and cultural friction.

Like Kodak: it risks protecting legacy ads for too long.

Like Fujifilm: it has the talent, money, and infrastructure to pivot — if it truly embraces AI platforms and is willing to cannibalize search ads.

Future Scenarios:

Assumption 1.

As people develop deep personal histories of satisfactory teamwork with their preferred SmartBot — leading to them to depend on their services and knowledge of prior conversations — then a majority of users will begin to buy services from their preferred SmartBot. It may take five years for the SmartBot business to be profitable for any of their providers.

The economics of providing SmartBot services right now are horrendous. The costs far outweigh the revenues.

Today, OpenAI’s ChatGPT has the largest estimated share of daily SmartBot users but subscription fees are not enough for OpenAI to break even. Estimates vary but OpenAI appears to have lost something on the order of more than $5 billion in 2024 and 2025 looks worse. Source: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/CCQsQnCMWhJcCFY9x/openai-lost-usd5-billion-in-2024-and-its-losses-are.

Meanwhile usage is broad and climbing. (See Similarweb for a vast array of user data. https://www.demandsage.com/chatgpt-statistics/#:~:text=ChatGPT%20Plus%20has%20gained%20over,2%20million%20in%20February%202025.)

Assumption 2.

Optimistic scenario (0.3 probability): Gemini becomes the leading SmartBot (as measured by number of user transactions it services) and user payments for SmartBot services replace the bulk of search ad revenue by the end of this decade (trends should become clear by 2027.)

Assumption 3.

Pessimistic scenario (0.7 probability) Search ad margins erode faster than Gemini, creating a “Kodak trap,” where legacy business funds but blocks reinvention. Where is the modeling for the financial transition?

Net on Alphabet’s future

Alphabet’s future primarily depends on how fast and boldly it cannibalizes its search ad business. If it embraces that pain effectively (like Netflix or Adobe), it can thrive. If it hesitates (like Kodak did), it risks long-term decline.